Studies of tenant farming within the Arkansas Delta have

focused mainly on the labor activism associated with the

Southern Tenant Farmers' Union and the sharecropping

systems of the southeastern region of the state. Social

histories of the state reveal how the system supported

inequitable and oppressive labor relations that continue

to contribute to the region's legacy of poverty. Labor union

activities of the 1930s and 40s, in particular, provide an

inspiring story that Studies of tenant farming within the

Arkansas Delta have focused mainly on the labor activism

associated with the Southern Tenant Farmers’ Union and

the sharecropping systems of the southeastern region of the

state. Social histories of the state reveal how the system

supported inequitable and oppressive labor relations that

continue to contribute to the region’s legacy of poverty. Labor

union activities of the 1930s and 40s, in particular, provide

an inspiring story that is preserved in scholarship and in a

museum located in Tyronza, Arkansas, where the union was

originally based. The preservation and interpretation of this

history contributes to our understanding of America’s regional

history, especially in relation to agriculture, labor, and race

relations. Sherry Laymon’s book adds to our understanding of

tenant farming by looking at agricultural history in a region of

northeastern Arkansas. Her study of Paul Pfeiffer’s farming

operations opens up a more richly-nuanced understanding of

Arkansas’s social history. Integrating oral history and studies

of vernacular architecture into her study, Laymon shows that

the sharecropper/tenant farming system was not necessarily an

exploitive

system.

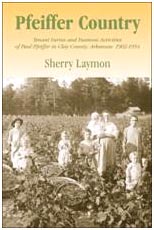

Laymon’s study centers on the life of Iowa businessman, Paul Pfeiffer, and his contributions to developing the area around Piggott, Arkansas. Pfeiffer moved from Iowa to St. Louis, eventually settling in this small town near the Missouri border in 1913. Pfeiffer came from a family of economic means. While he was opening up the area for cotton cultivation, his brothers were laying the foundation for a drug company that eventually became Pfeiffer Pharmaceuticals. Paul and Mary Pfeiffer lived in Piggot for the remainder of their lives, and they remained important entrepreneurs and civic leaders within the mid-south region. One of their daughters, Pauline Pfeiffer, went on to become a journalist, and she is remembered, today, as the second wife of Ernest Hemingway. The famous American writer, himself, spent much of his time in Piggott in the 1930s, and the Pfeiffer home is preserved today as a museum and interpretive center, complete with a redecorated presentation of Hemingway’s study. The Hemingway-Pfeiffer Museum and Educational Center graciously allowed Laymon to use oral histories, museum holdings, and archival information for her research.

Laymon’s book provides a fine overview of the Pfeiffer family’s activities in this northeastern Arkansas community. She uses a variety of sources to give the context for the Pfeiffers’ move to Piggott, and makes fine use of oral histories of current residents who rented land or worked for the family. Laymon then gives us an overview of the vernacular architecture associated with what have become known as “Pfeiffer Farms” within the Piggott community, and she analyzes the buildings in relation to regional styles of architecture and the agricultural system used by Pfeiffer. Laymon’s study convincingly shows that Pfeiffer blended together two economic systems to create an innovative, even benevolent, model for farming in the Arkansas Delta. Pfeiffer blended practices from real estate development with the tenant farming system to establish profitable farmsteads that contributed to his family’s fortune while also allowing his tenants opportunities for economic advancement. Unlike other planters, Pfeiffer eschewed highly exploitive practices, such as creating an economic hegemony through operation of commissaries and patrols, and instead displayed a benevolence to his tenants by renegotiating—and sometimes even forgiving—loans. Laymon backs her conclusions about these socially responsible practices through thorough written documentation, and she also presents numerous stories of the Pfeiffers’ largesse throughout her narrative. She also shows that Paul Pfeiffer’s unique blending of tenant farming with real estate development did, in fact, allow many renters to eventually purchase their own farms.

What emerges in Pfeiffer’s system is a blending of the ideal of the midwestern family farm with southern sharecropping. This hybrid system is clearly evident in Laymon’s intriguing presentation of vernacular architecture. Although few Pfeiffer farms stand intact today, Laymon was able to create her own renderings based on recollections and sketches of older sites from local residents. Her illustrations show how the influence of predominantly midwestern styles of vernacular architecture often blended with southern building styles to create a unique impact on the region’s cultural landscape. One especially intriguing example of this process is her rich discussion of a regional adaptation of the shotgun house. Whereas most shotgun homes feature an asymmetrical façade with only one window on the gabled end, the Pfeiffer shotgun featured a central doorway flanked by two windows. This style does show up throughout the area, and it appealed to the aesthetic values of Pfeiffer when he hired builders to construct these homes. Through her analysis of the shotgun houses and other styles of homes, barns, and outbuildings, Laymon demonstrates how individual influences and regional adaptations are essential components of a localized vernacular style of architecture.

Pfeiffer Country is an important contribution to regional history, and Laymon’s blending of oral history with analysis of vernacular architecture will provide excellent methods for future studies. The book could benefit from a more thorough application of ideas from scholarship within these areas, and there also is an implicit dichotomy between “savage” and “civilized” that reveals itself in inopportune times throughout the book. This tension, however, feels more anachronistic than offensive, and Laymon gives us an excellent contribution for understanding Pfeiffer’s farms in relation to wider patterns of history and culture within the Arkansas Delta in particular, and southern social history in general.

Gregory Hansen

Professor of Folklore and English

Arkansas State University

Filed under: PFEIFFER COUNTRY: THE TENANT FARMS AND BUSINESS ACTIVITIES OF PAUL PFEIFFER IN CLAY COUNTY, ARKANSAS 1902-1954